Any number of metaphors might be used for the predicament today’s industrial societies face as the age of cheap energy stumbles to its end, but the one that keeps coming to mind is drawn from a scene in one of the favorite books of my childhood, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit. It’s the point in the story when Bilbo Baggins, the protagonist, gets lost in goblin-tunnels under the Misty Mountains and there encounters a gaunt, slippery, cannibalistic creature named Gollum.

That meeting was not exactly full of bonhomie. Gollum regarded Bilbo in much the way a hungry undergraduate regards the arrival of takeout pizza, but Bilbo was armed and alert. To put his intended meal off his guard, Gollum challenged Bilbo to a riddle contest. So there they sat, deep underground, challenging each other with the hardest riddles they could think of. I sometimes think the rock around Gollum’s lair must have been a Jurassic sandstone full of crude oil; if Gollum were around nowadays, equally, I suspect he would be shilling for Cambridge Energy Research Associates, purveying energy misinformation to the media, and his “Preciousss” would be made of black gold. Certainly, though, the world’s industrial societies right now are in much the same predicament as Bilbo, fumbling in the dark for answers to riddles that take on an increasingly threatening tone with each moment that passes.

I’d like to talk about three of those riddles now. None of them are insoluble, but they point to a profoundly unwelcome reality that will play a major role in shaping the economics of the age dawning around us right now – and unlike characters in a children’s novel, we can’t count on being bailed out of our predicament, as Bilbo was, by the unexpected discovery of a magic ring. Here they are:

First: It is the oldest machine in the world; it has raised the world’s greatest monuments and destroyed most of them, saved lives by the millions and killed them in like number; and when it is not in use, no one can see it. What is it?

Second: There is a thoroughly proven, economically viable way to use solar energy that requires no energy subsidy from fossil fuels at all, and every mainstream economist thinks that getting rid of it wherever possible is the key to prosperity. What is it?

Third: Two workers in different countries work in identical factories, using identical tools to make identical products. One of them makes twenty dollars an hour plus a benefit package; the other makes two dollars a day with no benefits at all. Why is that?

The last one is the easiest, though you’ll have a hard time finding a single figure in American public life who will admit to the answer. It’s not considered polite these days to talk about America’s empire, despite the fact that we keep troops in 140 other countries, and the far from unrelated fact that the 5% of Earth’s population that live in the US use around a third of the world’s resources, energy, and consumer products. Like every other empire, we have a tribute economy; we dress it up in free-market drag by giving our trading partners mountains of worthless paper in return for the torrents of real wealth that flow into the US every day; but the result, now as in the past, is that the imperial nation and its inner circle of allies have a vast surplus of wealth sloshing through their economies. Handing over a little of that extra wealth to the poor and the working class has proven to be a tolerably effective way to maintain some semblance of social order.

That habit has been around nearly as long as empires themselves; the Romans were particularly adept at it -- “bread and circuses” is the famous phrase for their policy of providing free food and entertainment to the Roman urban poor o keep them docile. Starting in the wake of the last Great Depression, when many wealthy people woke up to the fact that their wealth did not protect them against bombs tossed through windows, most industrial nations have done the same thing by ratcheting up working class incomes and providing benefits such as old age pensions. No doubt a similar logic motivated the recent rush to force through a national health care system in the US, though the travesty that resulted is likely to cause far more unrest than it quells.

More generally, what passes by the name of democracy these days is a system in which factions of the political class buy votes from pressure groups by handing out what the political slang of an earlier day called by the endearing name of “pork.” The imperial tribute economy provided ample resources for political pork vendors, and the resulting outpouring of pig product formed a rising tide that, as the saying goes, lifted all boats. The problem, of course, is the same problem that afflicted Britain’s domestic economy during its age of empire, and Spain’s before that, and so on down through history: when wages in an imperial nation rise far enough above those of its neighbors, it stops being profitable to hire people in the imperial nation for any task that can be done outside it.

The result is a society in which those who get access to pork prosper, and those who don’t are left twisting in the wind. Arnold Toynbee, whose monumental study of the rise and fall of empires remains the most detailed examination of the process, calls these latter the “internal proletariat”: those who live within an imperial society but no longer share in its benefits, and become increasingly disaffected from its ideals and institutions. In the near term, they are the natural fodder of demagogues; in the longer term, they make common cause with the “external proletariat” – those nations outside the imperial borders whose labor and resources have become essential to the imperial economy, but who receive no benefits from that economy – and play a key role in bringing the whole system crashing down.

One of the ironies of the modern world is that today’s economists, so many of whom pride themselves on their realism, have by and large ignored the political dimensions of economics, and retreated into what amounts to a fantasy world in which the overwhelming influence of political considerations on economic life is denounced as an aberration where it is acknowledged at all. What Adam Smith and his successors called “political economy” suffered the amputation of its first half once Marx showed that it could be turned into an instrument for rabblerousing. Thus the economists who support the current versions of bread and circuses labor to find specious economic reasons for what, after all, is a simple political payoff. Meanwhile, those who oppose them have lost track of the very real possibility that those who are made to go hungry in the presence of abundance may embrace options entirely outside of the economic realm, such as the aforementioned bombs through windows.

This irony is compounded by the fact that very nearly every economist in the profession, liberal or conservative, accepts certain presuppositions that work overtime to speed the process by which the working class becomes an internal proletariat in Toynbee’s sense, hastening the breakdown of the society these economists claim to interpret. It takes a careful ear for the subtleties of economic jargon to understand how this works. Economists talk constantly about efficiency and productivity, but they rarely say in so many words is what these terms mean.

A glance inside any economics textbook will clue you in. By efficiency, economists mean labor efficiency – that is, how much or little of human labor is needed for any given economic task. By productivity, in turn, economists mean labor productivity – that is, how much value is created per unit of labor. Thus anything that decreases the number of employee hours needed to produce a given quantity of goods and services counts as an increase in efficiency and productivity, whether or not it is efficient or productive in any other sense.

There’s a reason for this rather odd habit, and it points up one of the central issues of the industrial world’s present predicament. In the industrial world, for the last century or more, labor costs have been the single largest expense for most business enterprises, in large part because of the upward pressure on living standards caused by the tribute economy. Meanwhile the cost of natural resources and energy have been kept down by the same imperial arrangements. The result is a close parallel to Liebig’s Law, one of the fundamental principles of ecology. Liebig’s Law holds that the nutrient in shortest supply puts a ceiling on the growth of living things, irrespective of the availability of anything more abundant; in the same way, our economics have evolved to treat the costliest resource to hand, human labor, as the main limitation to economic growth, and to treat anything that decreases the amount of labor as an economic gain.

Even when the energy needed to power machines was still cheap and abundant, this way of thinking was awash with mordant irony, because only in times of relatively robust economic growth did workers who were rendered surplus by such “productivity gains” readily find jobs elsewhere. At least as often, they added to the rolls of the unemployed, or pushed others onto those rolls, fueling the growth of an impoverished underclass that formed the seed of today’s rapidly growing internal proletariat. With the end of the age of cheap energy, though, the fixation on labor efficiency promises to become a millstone around the neck of America’s economy and, from a wider perspective, that of the world as a whole.

A world that has nearly seven billion people on it and a rapidly dwindling supply of fossil fuels, after all, has better ways to manage its affairs than those based on the assumption that putting people out of work and replacing them with fossil fuels is the way to prosperity. This is one of the unlearned lessons of the global economy that is now coming to an end around us. While it was billed by friends and foes alike as the final triumph of corporate capitalism, globalization can more usefully be understood as an attempt by a failing system to prop up the illusion of economic growth by transferring the production of goods and services to economies that are, by the standards just mentioned, less efficient than those of the industrial world. Without the distorting effects of an imperial tribute economy, labor proved to be enough cheaper than energy that the result was profitable, and allowed the world’s industrial nations to maintain their exaggerated standards of living for a few more years.

At the same time, the brief heyday of the global economy was only made possible by a glut of petroleum that made transportation costs negligible. That glut is ending as world oil production begins to slip down the far side of Hubbert’s curve, while the Third World nations that profited most by globalization cash in their newfound wealth for a larger share of the world’s energy resources, putting further pressure on a balance of power that is already tipping against the United States and its allies. As this process continues, the tribute economy will be an early casualty. The implications for the lifestyles of most Americans will not be welcome.

I have suggested in previous posts that one useful way to think about the transformations now under way is to see them as the descent of the United States to Third World status. One consequence of that process is that most Americans, in the not very distant future, will earn the equivalent of a Third World income. It’s unlikely that their incomes will actually drop to $2 a day; far more likely is that the value of the dollar will crumple, so that a family making $40,000 a year might expect to pay half that to keep itself fed on rice and beans, and the rest to buy cooking fuel and a few other necessities.

It’s hard to see any way such a decline in our collective wealth could take place without political explosions on the grand scale. Still, in the twilight of the age of cheap energy, the most abundant energy source remaining throughout the world will be human labor, and as other resources become more costly, the price of labor – and thus the wages that can be earned by it – will drop accordingly.

At the same time, human labor has certain crucial advantages in a world of energy scarcity. Unlike other ways of getting work done, which generally require highly concentrated energy sources, human labor is fueled by food, which is a form of solar energy. Our agricultural system produces food using fossil fuels, but this is a bad habit of an age of abundant energy; field labor by human beings with simple tools, paid at close to Third World wages, already plays a crucial role in the production of many crops in the US, and this will only increase as wages drop and fuel prices rise.

The agriculture of the future, like agriculture in any thickly populated society with few energy resources, will thus use land intensively rather than extensively, rely on human labor with hand tools rather than more energy-intensive methods, and produce bulk vegetable crops and relatively modest amounts of animal protein; the agricultural systems of medieval China and Japan, chronicled by F.H. King in Farmers of Forty Centuries, are as good a model as any. Such an agricultural system will not support seven billion people, but then neither will anything else, and a decline in population as malnutrition becomes common and public health collapses is a sure bet for the not too distant future.

For similar reasons, the economies of the future will make use of human labor, rather than any of the currently fashionable mechanical or electronic technologies, as their principal means for getting things done. Partly this will happen because in an overcrowded world where all other resources are scarce and costly, human labor will be the cheapest resource available, but it draws on another factor as well.

This was pointed out many years ago by Lewis Mumford in The Myth of the Machine. He argued that the revolutionary change that gave rise to the first urban civilizations was not agriculture, or literacy, or any of the other things most often cited in this context. Instead, he proposed, that change was the invention of the world’s first machine – a machine distinguished from all others in that all of its parts were human beings. Call it an army, a labor gang, a bureaucracy or the first stirrings of a factory system; in these cases and more, it consisted of a group of people able to work together in unison. All later machines, he suggested, were attempts to make inanimate things display the singleness of purpose of a line of harvesters reaping barley or a work gang hauling a stone into place on a pyramid.

That kind of machine has huge advantages in an world of abundant population and scarce resources. It is, among other things, a very efficient means of producing the food that fuels it and the other items needed by its component parts, and it is also very efficient at maintaining and reproducing itself. As a means of turning solar energy into productive labor, it is somewhat less efficient than current technologies, but its simplicity, its resilience, and its ability to cope with widely varying inputs give it a potent edge over these latter in a time of turbulence and social decay.

That kind of machine, it deserves to be said, is also profoundly repellent to many people in the industrial world, doubtless including many of those who are reading this essay. It’s interesting to think about why this should be so, especially when some examples of the machine at work – Amish barn raisings come to mind – have gained iconic status in the alternative scene. It is not going too far, I think, to point out that the word “community,” which receives so much lip service these days, is in many ways another word for Mumford’s primal machine. For the last few centuries, we have tried replacing that machine with a dizzying assortment of others; instead of subordinating individual desires to collective needs, like every previous society, we have built a surrogate community of machines powered by coal and oil and natural gas to take care, however sporadically, of our collective needs. As those resources deplete, societies used to directing nonhuman energy according to scientific principles will face the challenge of learning once again how to direct human energy according to older and less familiar laws. This can be done in relatively humane ways, or in starkly inhuman ones; what remains to be seen is where along this spectrum the societies of the future will fall. That riddle neither Bilbo nor Gollum could have answered, and neither can I.

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

Sunday, March 28, 2010

Thursday, March 25, 2010

Adnan Buyung Nasution is professor

Founder Of The legal aid institutions (LBH) in Indonesia, DR. Adnan Buyung Nasution, defined as a professor of the Univerity of Melbourne, Australia in January. appointment as the new professor announced Tuesday 16 March 2010.

Founder Of The legal aid institutions (LBH) in Indonesia, DR. Adnan Buyung Nasution, defined as a professor of the Univerity of Melbourne, Australia in January. appointment as the new professor announced Tuesday 16 March 2010.bang-Buyung-so he called. defined as a professor because perseverance to advance the science of law, law enforcement and justice, and the continuous struggle in the respect and human rights for half a century.

Melbourne University law fakulatas very proud of you "because you has also been a study here a few years ago, the contents of the letter of appointment. Signed by the Dean of Faculty of Melbourne University law" professor Michael Commelin AO ".

Adnan B. Nasution was able to hold the title of professor began early in 2010. with the appointment, Bang-Buyung get various facilities from the university, like any other professor. adnan professor nasution pitcher can not determine when they will give a public lecture in Melbourne because his work is still very busy.

From the newspaper "Kompas" today "25 march 2010"

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

The Logic of Abundance

The last several posts here on The Archdruid Report have focused on the ramifications of a single concept – the importance of energy concentration, as distinct from the raw quantity of energy, in the economics of the future. This concept has implications that go well beyond the obvious, because three centuries of unthinking dependence on highly concentrated fossil fuels have reshaped not only the economies and the cultures of the industrial West, but some of our most fundamental assumptions about the universe, in ways all too likely to be disastrously counterproductive in the decades and centuries ahead of us.

Ironically enough, given the modern world’s obsession with economic issues, one of the best examples of this reshaping of assumptions by the implications of cheap concentrated energy has been the forceful resistance so many of us put up nowadays to thinking about technology in economic terms. It should be obvious that whether or not a given technology or suite of technologies continues to exist in a world of depleting resources depends first and foremost on three essentially economic factors. The first is whether the things done by that technology are necessities or luxuries, and if they are necessities, just how necessary they are; the second is whether the same things, or at least the portion of them that must be done, can be done by another technology at a lower cost in scarce resources; the third is how the benefits gained by keeping the technology supplied with the scarce resources it needs measures up to the benefits gained by putting those same resources to other uses.

Nowadays, though, this fairly straightforward calculus of needs and costs is anything but obvious. If I suggest in a post here, for example, that the internet will fail on all three counts in the years ahead of us – very little of what it does is necessary; most of the things it does can be done with much less energy and resource use, albeit at a slower pace, by other means; and the resources needed to keep it running would in many cases produce a better payback elsewhere – you can bet your bottom dollar that a good many of the responses will ignore this analysis entirely, and insist that since it’s technically possible to keep the internet in existence, and a fraction of today’s economic and social arrangements currently depend on (or at least use) the internet, the internet must continue to exist. Now it’s relevant to point out that the world adapted very quickly to using email and Google in place of postage stamps and public libraries, and will doubtless adapt just as quickly to using postage stamps and libraries in place of email and Google if that becomes necessary, but this sort of thinking – necessary as it will be in the years to come – finds few takers these days.

This notion that technological progress is a one-way street not subject to economic limits invites satire, to be sure, and I’ve tried to fill that need more than once in the past. Still, there are deep issues at work that also need to be addressed. One of them, which I’ve discussed at length elsewhere, is the way that progress has taken on an essentially religious value in the modern world, especially but not only among those who reject every other kind of religious thinking. Still, there’s another side to it, which is that for the last three hundred years those who believed in the possibilities of progress have generally been right. There have been some stunning failures to put alongside the successes, to be sure, but the trajectory that reached its climax with human footprints on the Moon has provided a potent argument supporting the idea that technological complexity is cumulative, irreversible, and immune to economic concerns.

The problem with that argument is that it takes the experience of an exceptional epoch in human history as a measure for human history as a whole. The three centuries of exponential growth that put those bootprints on the gray dust of the Sea of Tranquillity were made possible by the conjunction of historical accidents and geological laws that allowed a handful of nations to seize the fantastic treasure of highly concentrated energy buried in the Earth’s fossil fuels and burn through it at ever-increasing rates, flooding their economies with almost unimaginable amounts of cheap and highly concentrated energy. It’s been fashionable to assume that the arc of progress was what made all that energy available, but there’s very good reason to think that this puts the cart well in front of the horse. Rather, it was the huge surpluses of available energy that made technological progress both possible and economically viable, as inventors, industrialists, and ordinary people all discovered that it really was cheaper to have machines powered by fossil fuels take over jobs that had been done for millennia by human and animal muscles, fueled by solar energy in the form of food.

The logic of abundance that was made plausible as well as possible by those surpluses has had impacts on our society that very few people in the peak oil scene have yet begun to confront. For example, many of the most basic ways that modern industrial societies handle energy make sense only if fossil fuel energy is so cheap and abundant that waste simply isn’t something to worry about. One of this blog’s readers, Sebastien Bongard, pointed out to me in a recent email that on average, only a third of the energy that comes out of electrical power plants reaches an end user; the other two-thirds are converted to heat by the electrical resistance of the power lines and transformers that make up the electrical grid. For the sake of having electricity instantly available from sockets on nearly every wall in the industrial world, in other words, we accept unthinkingly a system that requires us to generate three times as much electricity as we actually use.

In a world where concentrated energy sources are scarce and expensive, many extravagances of this kind will stop being possible, and most of them will stop being economically feasible. In a certain sense, this is a good thing, because it points to ways in which nations facing crisis because of a shortage of concentrated energy sources can cut their losses and maintain vital systems. It’s been pointed out repeatedly, for example, that the electrical grids that supply power to homes and businesses across the industrial world will very likely stop being viable early on in the process of contraction, and some peak oil thinkers have accordingly drawn up nightmare scenarios around the sudden and irreversible collapse of national power grids. Like most doomsday scenarios, though, these rest on the unstated and unexamined assumption that everybody involved will sit on their hands and do nothing as the collapse unfolds.

In this case, that assumption rests in turn on a very widespread unwillingness to think through the consequences of an age of contracting energy supplies. The managers of a power grid facing collapse due to a shortage of generation capacity have one obvious alternative to hand: cutting nonessential sectors out of the grid for as long as necessary, so the load on the grid decreases to a level that the available generation capacity can handle. In an emergency, for example, many American suburbs and a large part of the country’s nonagricultural rural land could have electrical service shut off completely, and an even larger portion of both could be put on the kind of intermittent electrical service common in the Third World, without catastrophic results. Of course there would be an economic impact, but it would be modest in comparison to the results of simply letting the whole grid crash.

Over the longer term, just as the twentieth century was the era of rural electrification, the twenty-first promises to be the era of rural de-electrification. The amount of electricity lost to resistance is partly a function of the total amount of wiring through which the current has to pass, and those long power lines running along rural highways to scattered homes in the country thus account for a disproportionate share of the losses. A nation facing prolonged or permanent shortages of electrical generating capacity could make its available power go further by cutting its rural hinterlands off the power grid, and leaving them to generate whatever power they can by local means. Less than a century ago, nearly every prosperous farmhouse in the Great Plains had a windmill nearby, generating 12 or 24 volts for home use whenever the wind blew; the same approach will be just as viable in the future, not least because windmills on the home scale – unlike the huge turbines central to most current notions of windpower – can be built by hand from readily available materials. (Skeptics take note: I helped build one in college in the early 1980s using, among other things, an old truck alternator and a propeller handcarved from wood. Yes, it worked.)

Steps like this have seen very little discussion in the peak oil scene, and even less outside it, because the assumptions about technology discussed earlier in this post make them, in every sense of the word, unthinkable. Most people in the industrial world today seem to have lost the ability to imagine a future that doesn’t have electricity coming out of a socket in every wall, without going to the other extreme and leaning on Hollywood clichés of universal destruction. The idea that some of the most familiar technologies of today may simply become too expensive and inefficient to maintain tomorrow is alien to ways of thought dominated by the logic of abundance.

That blindness, however, comes with a huge price tag. As the age of abundance made possible by fossil fuels comes to its inevitable end, a great many things could be done to cushion the impact. Quite a few of these things could be done by individuals, families, and local communities – to continue with the example under discussion, it would not be that hard for people who live in rural areas or suburbs to provide themselves with backup systems using local renewable energy to keep their homes viable in the event of a prolonged, or even a permanent, electrical outage. None of the steps involved are hugely expensive, most of them have immediate payback in the form of lower energy bills, and local and national governments in much of the industrial world are currently offering financial incentives – some of them very robust – to those who do them. Despite this, very few people are doing them, and most of the attention and effort that goes into responses to a future of energy constraints focuses on finding new ways to pump electricity into a hugely inefficient electrical grid, without ever asking whether this will be a viable response to an age when the extravagance of the present day is no longer an option.

This is why attention to the economics of energy in the wake of peak oil is so crucial. Could an electrical grid of the sort we have today, with its centralized power plants and its vast network of wires bringing power to sockets on every wall, remain a feature of life throughout the industrial world in an energy-constrained future? If attempts to make sense of that future assume that this will happen as a matter of course, or start with the unexamined assumption that such a grid is the best (or only) possible way to handle scarce energy, and fixate on technical debates about whether and how that can be made to happen, the core issues that need to be examined slip out of sight. The question that has to be asked instead is whether a power grid of the sort we take for granted will be economically viable in such a future – that is, whether such a grid is as necessary as it seems to us today; whether the benefits of having it will cover the costs of maintaining and operating it; and whether the scarce resources it uses could produce a better return if put to work in some other way.

Local conditions might provide any number of answers to that question. In some countries and regions, where people live close together and renewable energy sources such as hydroelectric power promise a stable supply of electricity for the relatively long term, a national grid of the current type may prove viable. In others, as suggested above, it might be much more viable to have restricted power grids supplying urban areas and critical infrastructure, while rural hinterlands return to locally generated power or to non-electrified lifestyles. In still others, a power grid of any kind might prove to be economically impossible.

Under all these conditions, even the first, it makes sense for governments to encourage citizens and businesses to provide as much of their own energy needs as possible from locally available, diffuse energy sources such as sunlight and wind. (It probably needs to be said, given current notions about the innate malevolence of government, that whatever advantages might be gained from having people dependent on the electrical grid would be more than outweighed by the advantages of having a work force, and thus an economy, that can continue to function on at least a minimal level if the grid goes down.) Under all these conditions, it makes even more sense for individuals, families, and local communities to take such steps themselves, so that any interruption in electrical power from the grid – temporary or permanent – becomes an inconvenience rather than a threat to survival.

A case could easily be made that in the face of a future of very uncertain energy supplies, alternative off-grid sources of space heating, hot water, and other basic necessities are as important in a modern city as life jackets are in a boat. An even stronger case could be made that individuals and groups who hope to foster local resilience in the face of such a future probably ought to make such simple and readily available technologies as solar water heating, solar space heating, home-scale wind power, and the like central themes in their planning. Up to now, this has rarely happened, and the hold of the logic of abundance on our collective imagination is, I think, a good part of the reason why.

What makes this even more important is that the electrical power grid is only one example, if an important one, of a system that plays a crucial role in the way people live in the industrial world today, but that only makes sense in a world where energy is so abundant that even huge inefficiencies don’t matter. It’s hardly a difficult matter to think of others. To think in these terms, though, and to begin to explore more economical options for meeting individual and community needs in an age of scarce energy, is to venture into a nearly unexplored region where most of the rules that govern contemporary life are stood on their heads. We’ll map out one of the more challenging parts of that territory in next week’s post.

Ironically enough, given the modern world’s obsession with economic issues, one of the best examples of this reshaping of assumptions by the implications of cheap concentrated energy has been the forceful resistance so many of us put up nowadays to thinking about technology in economic terms. It should be obvious that whether or not a given technology or suite of technologies continues to exist in a world of depleting resources depends first and foremost on three essentially economic factors. The first is whether the things done by that technology are necessities or luxuries, and if they are necessities, just how necessary they are; the second is whether the same things, or at least the portion of them that must be done, can be done by another technology at a lower cost in scarce resources; the third is how the benefits gained by keeping the technology supplied with the scarce resources it needs measures up to the benefits gained by putting those same resources to other uses.

Nowadays, though, this fairly straightforward calculus of needs and costs is anything but obvious. If I suggest in a post here, for example, that the internet will fail on all three counts in the years ahead of us – very little of what it does is necessary; most of the things it does can be done with much less energy and resource use, albeit at a slower pace, by other means; and the resources needed to keep it running would in many cases produce a better payback elsewhere – you can bet your bottom dollar that a good many of the responses will ignore this analysis entirely, and insist that since it’s technically possible to keep the internet in existence, and a fraction of today’s economic and social arrangements currently depend on (or at least use) the internet, the internet must continue to exist. Now it’s relevant to point out that the world adapted very quickly to using email and Google in place of postage stamps and public libraries, and will doubtless adapt just as quickly to using postage stamps and libraries in place of email and Google if that becomes necessary, but this sort of thinking – necessary as it will be in the years to come – finds few takers these days.

This notion that technological progress is a one-way street not subject to economic limits invites satire, to be sure, and I’ve tried to fill that need more than once in the past. Still, there are deep issues at work that also need to be addressed. One of them, which I’ve discussed at length elsewhere, is the way that progress has taken on an essentially religious value in the modern world, especially but not only among those who reject every other kind of religious thinking. Still, there’s another side to it, which is that for the last three hundred years those who believed in the possibilities of progress have generally been right. There have been some stunning failures to put alongside the successes, to be sure, but the trajectory that reached its climax with human footprints on the Moon has provided a potent argument supporting the idea that technological complexity is cumulative, irreversible, and immune to economic concerns.

The problem with that argument is that it takes the experience of an exceptional epoch in human history as a measure for human history as a whole. The three centuries of exponential growth that put those bootprints on the gray dust of the Sea of Tranquillity were made possible by the conjunction of historical accidents and geological laws that allowed a handful of nations to seize the fantastic treasure of highly concentrated energy buried in the Earth’s fossil fuels and burn through it at ever-increasing rates, flooding their economies with almost unimaginable amounts of cheap and highly concentrated energy. It’s been fashionable to assume that the arc of progress was what made all that energy available, but there’s very good reason to think that this puts the cart well in front of the horse. Rather, it was the huge surpluses of available energy that made technological progress both possible and economically viable, as inventors, industrialists, and ordinary people all discovered that it really was cheaper to have machines powered by fossil fuels take over jobs that had been done for millennia by human and animal muscles, fueled by solar energy in the form of food.

The logic of abundance that was made plausible as well as possible by those surpluses has had impacts on our society that very few people in the peak oil scene have yet begun to confront. For example, many of the most basic ways that modern industrial societies handle energy make sense only if fossil fuel energy is so cheap and abundant that waste simply isn’t something to worry about. One of this blog’s readers, Sebastien Bongard, pointed out to me in a recent email that on average, only a third of the energy that comes out of electrical power plants reaches an end user; the other two-thirds are converted to heat by the electrical resistance of the power lines and transformers that make up the electrical grid. For the sake of having electricity instantly available from sockets on nearly every wall in the industrial world, in other words, we accept unthinkingly a system that requires us to generate three times as much electricity as we actually use.

In a world where concentrated energy sources are scarce and expensive, many extravagances of this kind will stop being possible, and most of them will stop being economically feasible. In a certain sense, this is a good thing, because it points to ways in which nations facing crisis because of a shortage of concentrated energy sources can cut their losses and maintain vital systems. It’s been pointed out repeatedly, for example, that the electrical grids that supply power to homes and businesses across the industrial world will very likely stop being viable early on in the process of contraction, and some peak oil thinkers have accordingly drawn up nightmare scenarios around the sudden and irreversible collapse of national power grids. Like most doomsday scenarios, though, these rest on the unstated and unexamined assumption that everybody involved will sit on their hands and do nothing as the collapse unfolds.

In this case, that assumption rests in turn on a very widespread unwillingness to think through the consequences of an age of contracting energy supplies. The managers of a power grid facing collapse due to a shortage of generation capacity have one obvious alternative to hand: cutting nonessential sectors out of the grid for as long as necessary, so the load on the grid decreases to a level that the available generation capacity can handle. In an emergency, for example, many American suburbs and a large part of the country’s nonagricultural rural land could have electrical service shut off completely, and an even larger portion of both could be put on the kind of intermittent electrical service common in the Third World, without catastrophic results. Of course there would be an economic impact, but it would be modest in comparison to the results of simply letting the whole grid crash.

Over the longer term, just as the twentieth century was the era of rural electrification, the twenty-first promises to be the era of rural de-electrification. The amount of electricity lost to resistance is partly a function of the total amount of wiring through which the current has to pass, and those long power lines running along rural highways to scattered homes in the country thus account for a disproportionate share of the losses. A nation facing prolonged or permanent shortages of electrical generating capacity could make its available power go further by cutting its rural hinterlands off the power grid, and leaving them to generate whatever power they can by local means. Less than a century ago, nearly every prosperous farmhouse in the Great Plains had a windmill nearby, generating 12 or 24 volts for home use whenever the wind blew; the same approach will be just as viable in the future, not least because windmills on the home scale – unlike the huge turbines central to most current notions of windpower – can be built by hand from readily available materials. (Skeptics take note: I helped build one in college in the early 1980s using, among other things, an old truck alternator and a propeller handcarved from wood. Yes, it worked.)

Steps like this have seen very little discussion in the peak oil scene, and even less outside it, because the assumptions about technology discussed earlier in this post make them, in every sense of the word, unthinkable. Most people in the industrial world today seem to have lost the ability to imagine a future that doesn’t have electricity coming out of a socket in every wall, without going to the other extreme and leaning on Hollywood clichés of universal destruction. The idea that some of the most familiar technologies of today may simply become too expensive and inefficient to maintain tomorrow is alien to ways of thought dominated by the logic of abundance.

That blindness, however, comes with a huge price tag. As the age of abundance made possible by fossil fuels comes to its inevitable end, a great many things could be done to cushion the impact. Quite a few of these things could be done by individuals, families, and local communities – to continue with the example under discussion, it would not be that hard for people who live in rural areas or suburbs to provide themselves with backup systems using local renewable energy to keep their homes viable in the event of a prolonged, or even a permanent, electrical outage. None of the steps involved are hugely expensive, most of them have immediate payback in the form of lower energy bills, and local and national governments in much of the industrial world are currently offering financial incentives – some of them very robust – to those who do them. Despite this, very few people are doing them, and most of the attention and effort that goes into responses to a future of energy constraints focuses on finding new ways to pump electricity into a hugely inefficient electrical grid, without ever asking whether this will be a viable response to an age when the extravagance of the present day is no longer an option.

This is why attention to the economics of energy in the wake of peak oil is so crucial. Could an electrical grid of the sort we have today, with its centralized power plants and its vast network of wires bringing power to sockets on every wall, remain a feature of life throughout the industrial world in an energy-constrained future? If attempts to make sense of that future assume that this will happen as a matter of course, or start with the unexamined assumption that such a grid is the best (or only) possible way to handle scarce energy, and fixate on technical debates about whether and how that can be made to happen, the core issues that need to be examined slip out of sight. The question that has to be asked instead is whether a power grid of the sort we take for granted will be economically viable in such a future – that is, whether such a grid is as necessary as it seems to us today; whether the benefits of having it will cover the costs of maintaining and operating it; and whether the scarce resources it uses could produce a better return if put to work in some other way.

Local conditions might provide any number of answers to that question. In some countries and regions, where people live close together and renewable energy sources such as hydroelectric power promise a stable supply of electricity for the relatively long term, a national grid of the current type may prove viable. In others, as suggested above, it might be much more viable to have restricted power grids supplying urban areas and critical infrastructure, while rural hinterlands return to locally generated power or to non-electrified lifestyles. In still others, a power grid of any kind might prove to be economically impossible.

Under all these conditions, even the first, it makes sense for governments to encourage citizens and businesses to provide as much of their own energy needs as possible from locally available, diffuse energy sources such as sunlight and wind. (It probably needs to be said, given current notions about the innate malevolence of government, that whatever advantages might be gained from having people dependent on the electrical grid would be more than outweighed by the advantages of having a work force, and thus an economy, that can continue to function on at least a minimal level if the grid goes down.) Under all these conditions, it makes even more sense for individuals, families, and local communities to take such steps themselves, so that any interruption in electrical power from the grid – temporary or permanent – becomes an inconvenience rather than a threat to survival.

A case could easily be made that in the face of a future of very uncertain energy supplies, alternative off-grid sources of space heating, hot water, and other basic necessities are as important in a modern city as life jackets are in a boat. An even stronger case could be made that individuals and groups who hope to foster local resilience in the face of such a future probably ought to make such simple and readily available technologies as solar water heating, solar space heating, home-scale wind power, and the like central themes in their planning. Up to now, this has rarely happened, and the hold of the logic of abundance on our collective imagination is, I think, a good part of the reason why.

What makes this even more important is that the electrical power grid is only one example, if an important one, of a system that plays a crucial role in the way people live in the industrial world today, but that only makes sense in a world where energy is so abundant that even huge inefficiencies don’t matter. It’s hardly a difficult matter to think of others. To think in these terms, though, and to begin to explore more economical options for meeting individual and community needs in an age of scarce energy, is to venture into a nearly unexplored region where most of the rules that govern contemporary life are stood on their heads. We’ll map out one of the more challenging parts of that territory in next week’s post.

Tuesday, March 23, 2010

Sunday, March 21, 2010

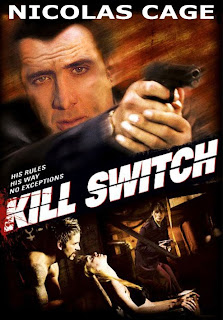

Nic Cage as Staff Sergeant William James

Mike Manning knows it HURTs getting stuffed in your LOCKER.

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)